The Bicycle Craze

Waltham's Contributions to the Fastest Wheels on Earth

By Amy Green, Ph.D., Charles River Museum historian

Raleigh advertisements provide a window into the world of bicycling, as the sport took the world by storm in the 1890s. The ever modernizing world ushered in a clock-ordered society, exemplified by time-discipline in the factory. This time-based form of constraint was transformed into an exciting discipline by new leisure activities like horse and bicycle racing: speed was a virtue; clocking time assessed athletic ability; and breaking records raised athletes to heroic status. Time challenged the competitor and entertained the spectator. Pictured here is A.A. Zimmerman, a feted cycling superstar, a three-time American national champion, who won over one-thousand races during his career.[1]

Perhaps as compelling in this ad are the two marginal figures on the grassy berm, a proper Victorian couple (note how each rider is fully covered, from top to tail) watching Zimmerman zip by in his racing shorts and sleeveless shirt. This Raleigh advertisement may feature Zimmerman, but it’s directed to the middle-class consumer, the leisure rider, both men and women, for whom the bicycle provided an efficient way of traveling, surpassing the horse, and furnished a new type of entertainment in the form of touring,

More radical in its impact on society was the lady’s bicycle. Great debates swirled around the appropriateness of the bicycle for women; but, with the rise of feminism and the suffragette movement during this period, female riders overcame the belief that cycling debased women and led to immorality The bike afforded women an outlet for exercise; it engineered physical freedom as bloomers were adopted for safe riding, worn often under a skirt used as concealment. It allowed women freedom to travel long distances and to join other men and women in the social experience of touring. In 1896, Susan B. Anthony said that “the bicycle had done more for the emancipation of women than anything else in the world.”[2] Women not only biked for business and pleasure, but they joined clubs and participated in races, just as men did. Bicycle racing became such an obsession for the public at large that cycling garnered more attention than America's national pastime, baseball, during the latter years of the nineteenth century. Even Arthur Conan Doyle preached the virtues of the bicycle in the Scientific American Magazine:

‘When the spirits are low, when the day appears dark, when work

becomes monotonous, when hope hardly seems worth having,

just mount a bicycle and go out for spin down the road, without

thought on anything but the ride you are taking.’[3]

Arthur Conan Doyle captures the essence of the modern leisure movement, a happy counterpart to the doldrums of work, and everyday life.

As early as 1878 (May 24th), the first recorded bike race in the United States took place in Boston’s Beacon Park. By 1897, four hundred factories in America produced two million bikes, while car manufacturers only assembled four thousand cars. So automobiles had yet to eclipse the bike as a favored mode of transportation. “For a decade … [bicycling] was all anybody wanted to talk about.”[4] The cycling heroes, who raced on newly laid oval tracks were paraded through cities. Racers “hurled themselves against the unknown of terrestrial velocity,” and scientists tried to explain these speeds and feats of fitness, to no avail. Dubbed the ‘“scorcher,’” the cyclist (in short sprints at least), was the fastest thing on earth, displaying new forms of athletic daring and dexterity.[5]

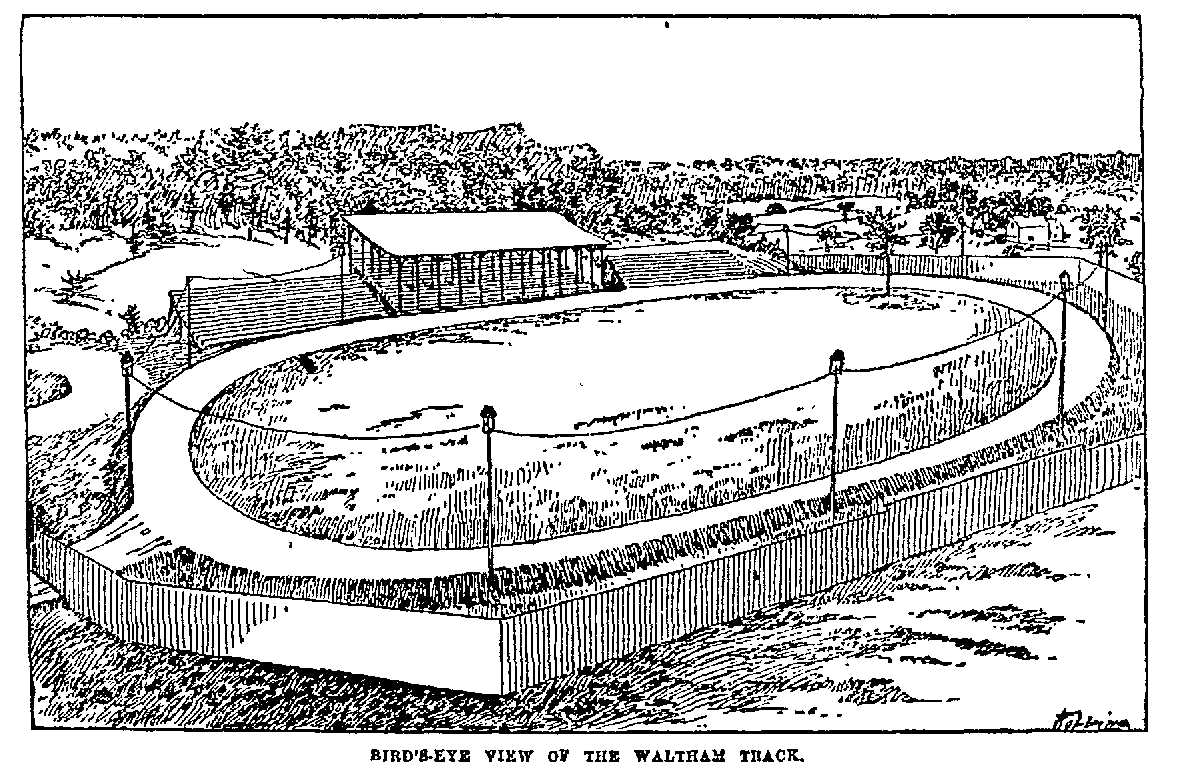

Waltham, Massachusetts not only rode the wave of the bicycle craze, it created its momentum as well. When Waltham opened its oval track in 1893, it established one of the fastest dirt tracks in the area, where many world records were set. It was the first track in Massachusetts devoted solely to bicycles, while other tracks were used for both bicycle racing and horse racing too--as tracking times with a stopwatch first emerged in the middle of the nineteenth century with the four-footed dynamo.

As one Smithsonian curator wrote, “speed had become a virtue” in America.[6] And this is nowhere more true than at bicycling parks, where speed not only gave rise to cycling superstars, but transfixed audiences around the country. The Waltham park could seat nine thousand people, and boasted a covered grandstand, “flanked by bleachers on both sides.”[7] And when it opened on Memorial Day in 1893, the organizers had to deal with an overflow crowd. Fifteen thousand spectators showed up! Around the track, spectators were crowded six people deep. Others found viewing on nearby hillsides, and on top of the neighboring Waltham hospital on South Street. And soon, the installation of electric lights allowed for nighttime racing.[8]

In Christopher Klein’s blog about the park, he quotes The Boston Globe’s response to the new Waltham race track:

‘There may be more beautiful spots within 10 miles of the State House than the one in which the new Waltham bicycle park lies. But it would take a week’s hunt to find them. The track sits among the hills in a sheltered valley like a jewel in a brooch, and the view from the grandstand is charming, and looks away to a low range of wooded hills.’[9]

In this instance, the Globe writer evinces a romantic strain, lauding the track, with inflated prose, for its park-like setting--a valley with wooded hills, “charming” to the eye. Racing becomes background to this writer’s (and the nation’s) increasing desire for untrammelled, outdoor spaces, away from the city. Yet, the two are not unrelated. America’s surge across the landscape atop highwheelers, for example, was part of an outdoor recreation movement that included other sports such as baseball, cricket, tennis, roller skating, polo, hunting, and many more.[10] This new enthusiasm for rugged, outdoor activity did not emerge in a vacuum. It was, in part, a response to the constraints of new urban life, the factory and its authoritarian structure and the home and its Victorian imperatives.